Refining the Additive Mind with Stephan Henrich

JULY 26, 2023 | Reading time: 6 min

Stephan Henrich is a designer and architect - and from this combination alone, you can probably already guess he has a very special approach to 3D printing. We spoke to Stephan about his passion for and the possibilities offered by additive manufacturing.

Stephan, how long have you been working with 3D printing, and how did you get started?

I first encountered 3D printing during my studies. After a few semesters in Stuttgart, I spent an exchange year in Paris in 2004 . 3D printing was already used in architecture back then, but it wasn't as widespread and established as today. During my stay, I worked with a well-known Paris architectural firm on a project with 3D printing models. That was the first time I didn't build the results of my planning work in the traditional way out of cardboard or wood. Straight from the computer into the real world, that was a defining moment.

Where are the limits for you regarding the design possibilities?

I have remained true to the technology and applied it to other areas, such as the field of textiles. I prefer to see the potential rather than the limits. The only real challenge is when it comes to large, bulky parts. However, this is offset by strengths such as functional integration, the reduction of the number of components and lightweight constructions. Since setting up my own studio in 2011, I have enjoyed moving between robotics, design and architecture, and specializing in design for additive manufacturing - in particular selective laser sintering. In the process, I realized that the limits have not yet been really explored, for example, in terms of flexible materials.

With the above in mind, which of your projects deserve a special mention?

At the moment I am very busy setting up my shoe and fashion label The Cryptide. I am fascinated by the idea of making shoes and textiles through additive manufacturing, with great demands on design and aesthetics. Remembering the various possibilities for customization. I have been wearing these sneakers for months and see massive potential because they work very well. I also have very positive memories of a project at Festo : the 3D Cocooner. This is a 3D printing robot that can build endless fiber-reinforced lattice structures freely in space.

Sounds exciting. We were also very impressed by the Fungus project. Please tell us more about this.

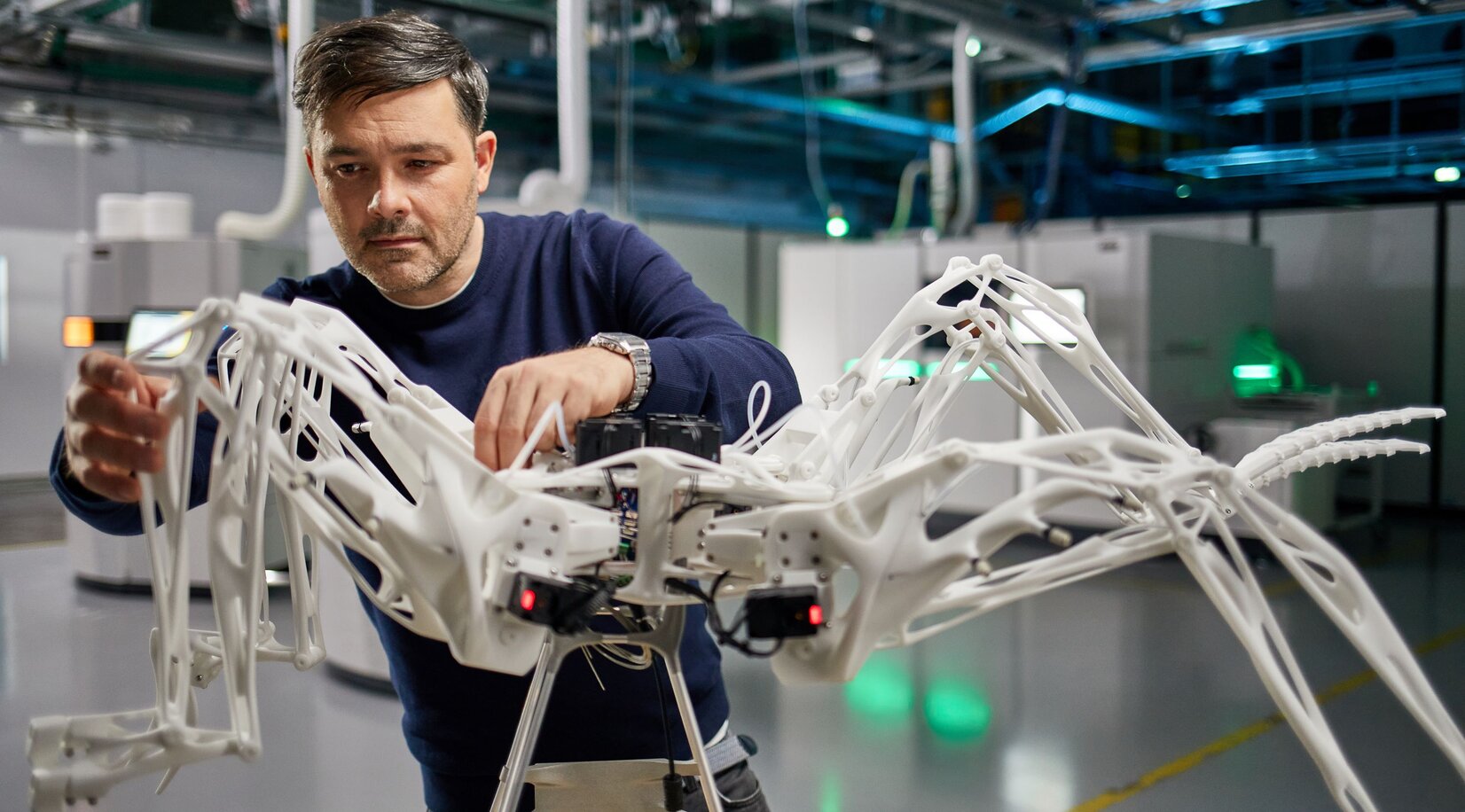

Definitely a very interesting project too. At present, we often have to choose between technology and nature. If technology spreads, nature has to give way. The Fungus project aims to resolve this supposed contrast. For this purpose, I developed a gardener robot as part of the project. Incidentally, it was manufactured with an EOS 3D printer using the bio-based material PA 11. The idea is to cultivate a vertical mushroom garden as part of a living architecture. The robot tends this garden so that mushroom harvests are possible. It’s like creating architecture that itself lives and integrates technology.

Considering this diversity and creativity, what would your advice be to other people to encourage more free thinking in design for 3D printing?

It may sound banal, but I come up with new solutions by consciously walking through the world and with my eyes open, without thinking of a specific project. I think of what things might look like if they had been designed to be manufactured by 3D printing. Ultimately, I always benefit when I manage to transfer my ideas into real projects. One example is the concept of bionics, where nature inspires us to come up with solutions. Whatever the case, the possibilities are almost endless. But having said that, it's still a process. You're not suddenly thrown into this vast space full of possibilities.

Since you are constantly breaking new ground: where and how to find inspiration?

An open mind, eyes, and curiosity are essential components. Likewise, a particular enthusiasm. This is how I find my inspiration in everyday life. Go outside, and actively experience the city or nature. When all is said and done, the perception of the real world is inspiration. It could be an afternoon in the playground with the kids. The kinematics of a piece of playground equipment is already living technology. There's an application of force, structures, and movements.

And how do you translate this inspiration into your projects?

(laughs) As it happens, I always have an A5 booklet in my pocket to jot down my ideas. These are based on my experience and the principles of construction. In my mind, I sometimes go one or more steps too far so that I can consciously question my approach and take something away again. Feedback from experts outside the specific field also plays a role, as does will and my passion for doing something different and hopefully better. The key is to find a meaningful application.

Is the design process easier if your project simplifies or improves a person's life or work?

This is the essential motivation in each and every project, but also at the meta-level. Now and then I'll get some feedback that my work has inspired someone, which is really nice. For me, however, motivation can also arise from interests, aesthetics, etc. Quite often, I simply like my job, which helps a lot. (laughs)

What are the essential differences between doing this kind of work you like and traditional design?

A generalization would be a bit presumptuous. Questioning things from the very beginning has proven to be vital for me. For example, if I want to achieve a specific functionality, I question the functionality itself wherever possible. A good example is my all-wheel-drive bike concept The Infinity Cruiser. Of course, bicycles have been around for a long time, and very good ones at that. So what could I change? That's why I have critically examined the components essential for a bicycle’s functionality. As a result, the bike now looks very different because the whole object has been fundamentally questioned. The principle applies to functionality as well as to aesthetics.

So, the clear idea that emerges in your projects always comes at the beginning?

I rarely take anything for granted. The starting point is usually the same. Anyone who questions something rarely comes up with the answer straight away. But if you don't do so, you often miss out on many possibilities, especially in an environment that offers so many creative opportunities.

What do you look for when designing for 3D printing, especially during a project?

For me, it is especially important to be economical with the material. I'm committed to the idea of lightweight constructions. In additive manufacturing, the lighter the part, the cheaper it becomes. The elegance and charm of 3D printing are also manifested in the art of omission. This means a little extra effort in planning. Instead of depicting something in three cuboids, a bone-like strut can save material - so the extra design effort pays off. In addition, it is ecologically worthwhile working in a way that conserves resources.

Design and architecture - a very special combination.

Do you believe someone without a background in architecture can open up new design worlds for themselves in a way similar to how you have done things?

Certainly in my eyes this is more a question of mind than any specific training. I have already mentioned the concept of a transfer. This is necessary for someone with an architectural background who wants to design products. Someone else, who may come from a graphic design or a scientific background, for example, will have developed their own methods to make the best use of their background while designing. The key is to listen to your inner self. To your wishes, your interests. If you take these seriously and find the proper context, you can open new doors for yourself and walk through them. It is also important to accept help and to question one's own actions healthily. You can certainly open up new design worlds if you have the self-confidence, courage, interest, and the right mindset.

Stephan Henrich works at the interface of architecture, narration, design, and robotics. He has been in charge of his office Stephan Henrich - Robotics Design and Architecture in Stuttgart since 2011, where he operates a robot lab and a small hardware production facility for prototype development, including an additive manufacturing workshop with selective laser sintering (SLS) equipment. Stephan Henrich is currently involved in developing an additive-generative production method based on biomaterials as a design tool in architecture and design. He is also preparing the launch of his own design label The Cryptide.

After studying architecture at the University of Stuttgart with a diploma in 2007 and the Ecole d'Architecture de Paris Belleville, Henrich worked in various architectural and engineering offices. At R&SIE(n) Architectes in Paris, he was an associate in numerous international projects. He oversaw the robotic handwriting project for the film "Marilyn" by the Parisian artist Philippe Parreno, thus bringing new life to the cinema legend's signature. He also developed the 3D Cocooner in Festo's Bionic Learning Network, a 3D printing robot that can build endless fiber-reinforced lattice structures freely in space. Stephan Henrich has also held various teaching posts at universities, including a visiting professorship at the University of Innsbruck.